Helene Schjerfbeck and The Collection of Stenman

The Finnish-Swedish artist Helene Schjerfbeck (1862-1946) is regarded to be one of the most prominent modernists of the 20th century. During her early years she painted figures with inspiration from the 19th century realist movement such as Sårad krigare from 1880. Only a year later, she painted Gosse matar lillasyster in a more naturalistic matter. The movement of impressionism also influenced Schjerfbeck’s works during this period, which the painting Byktork from 1883 is a fine example of. During the forthcoming century, she finally developed the minimalistic, reduced style with only a few details that has become synonymous with her impressive artistry. She has become most famous for her many intensive and unveiling self-portraits.

She was the 11-year-old wonder child who was admitted to the Finish Art society’s School of drawing in Helsinki, the current Finnish Fine Arts Academy. In 1880 when she was only 18 years old, she visited Paris for the first time. As a little girl, she had fallen and broken a hip, but as the family could not afford a visit to the doctor she remained limp for the rest of her life. Her father, who worked as a railway officer, passed away when Helene Schjerfbeck was 13 years old, which left her mother in charge of the financial support for Helene and her older brother Magnus Schjerfbeck (who later became the municipal architect in Helsinki). There was rarely meat on the table, but a strong cohesion. She spent twelve years of sometimes year-long study trips where she went to live in Paris in France, Pont-Aven in Brittany and later in St Ives in England. After copying the old Renaissance master’s works in St. Petersburg, Vienna and Florence she was asked to take a teaching position at her old school. Reluctantly, she said yes. She wanted to remain free within her artistry, but the economic uncertainty forced her to undertake the position. The difficulty of earning enough money on her paintings and the concerns regarding to face an old age without pension settled the case. During her ten years of teaching, she had less and less time to paint. In 1902, she left Helsinki and her teaching position for a life beyond the coteries, arguments between artists and a political unrest. She settled down in Hyvinkää, a railway junction about 50 kilometers north of Helsinki. Since she was unmarried, her mother accompanied her due to the customs at that time. The two of them lived together in one room and a kitchen until the death of her mother in 1923. After the death of her mother, Schjerfbeck got her own atelier. In 1925, she moved to Ekenäs but due to the war she had to keep moving house for the forthcoming years. During her two last years (1944-1946), she was evacuated to Sweden.

Gösta Stenman (1888-1947) rediscovered Helene Schjerfbeck, when he as a young art dealer visited her in Hyvinkää in 1913. She had just turned 50 years; he was only 30 years old. Stenman was a true entrepreneur, inspired by the life of artists in Paris, and he had an unerring sense for quality within art. He took great risks, lost sometimes but was always willing to start over. He opened his first Stenman Konstsalong (Stenman Art salon) in Helsinki in 1919. He had already then established the concept of Samling Stenman (Collection Stenman), with the recognizable character of a graphic designed stamp with a gothic “S” enclosed in a square. In 1934, during the interwar period, he moved to Sweden and opened his Art salon at Storgatan 10 in Stockholm. At the same time he became a Swedish citizen. In 1937 Stenman arranged the second solo exhibition of Schjerfbeck in exhibition spaces three floors up at his place in Stockholm. It was a veritable success! The art critic Gotthard Johansson was mesmerized and wrote “It is a holy place” when he reviewed her show. After the end of the exhibition, Stenman established a contract with Helene Schjerfbeck, which provided her with a secure monthly income and gave him access to everything she was working on. Collection Stenman included several young Finnish modernist artists such as Tyko Sallinen, Jalmari Ruokokoski and Valle Rosenberg, but also Swedish artists like Åke Göransson, Eva Bagge and Siri Derkert. He also owned a considerable amount of old master paintings.

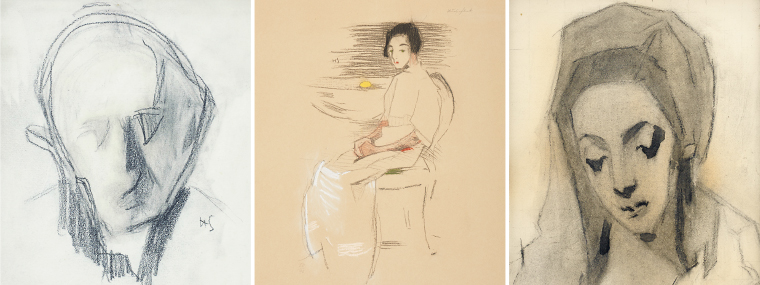

It was Gösta Stenman who encouraged Helene Schjerfbeck in 1938 to try graphical techniques and in particular lithography. Ever since her youth she had wanted to try to print lithographs, but never had the possibility due to economic reasons. She used six of her most valued paintings as a basis for many prints, The Convalescent, Picture Book, The Confirmation Candidate or Devotions, Costume Picture, Silk Shoes and At the Hearth. They were printed in many different editions and series/etat’s. She signed every print in the plate with her monogram HS, and when she numbered the edition she also signed them with pencil with her name in cursive. The artist never approved the print of the motif At the Hearth. With some of the prints, such as Costume Picture and At the Hearth, she tried in 1939 to add colour with the use of pastel to enhance the expression. This was very much appreciated by Gösta Stenman. In the winter of 1945-1946, during her last years, Helene Schjerfbeck enhanced another eight sheets with pastel, from the five motifs that she had approved for printing.

Lena Holger

Author and art historian

October 2016

Literature:

Camilla Hjelm, Modernismens förespråkare. Gösta Stenman och hans konstsalong. CAA 17. Helsinki: Finnish National Gallery 2009.

Lena Holger, Helene Schjerfbeck. Liv och konstnärskap. Stockholm: Raster förlag 1987.

Lena Holger, Helene Schjerfbeck. An Artist of Strong Integrity. Helsinki: Ateneum Art Museum/ Finnish National Gallery 2016.